“Her failure to appeal to her companions who were no others than her brother, her aunt and her lover, and her conduct in meekly following Ganpat appellant and allowing him to have his way with her to the extent of satisfying his lust in full, makes us feel that the consent in question was not a consent which could be brushed aside as “passive submission”.

Tuka Ram And Anr vs State Of Maharashtra, 1979 SCR (1) 810

It is said that the wheels of justice grind slow but they grind fine. However if one looks at how cases progress in Indian Courts it seems that justice is comfortable being at rest. This is incredibly relevant to a debate which is spurred with each act of sexual violence reported in the press. The motion for this starts with an increase in penalties (usually capital punishment), which is defended with some nuance that the law should aim for certainty of conviction rather than severity of punishment. Infact such proposals for an increase in penalties was debunked by the Justice Verma Committee Report, which called for a more concentrated effort towards the enforcement of existing law. It stated, “1. The existing laws, if faithfully and efficiently implemented by credible law enforcement agencies, are sufficient to maintain law and order and to protect the safety and dignity of the people, particularly women, and to punish any offenders who commit any crime. This is not to say that the necessary improvements in the law, keeping in mind modern times, should not be enacted at the earliest.”

Delay in general

Let’s look at some data first to get a sense of the problem. During the 2011, law day lecture Justice Kapadia, the then Chief Justice of India gave some staggering statistics with respect to the general trends on court cases. He stated that in 5 years (31.12.2005 to 31.12.2010) about 11.16 crore cases were filed in India out of which 10.77 crore were disposed by a total of 12,600 judges. For those who are fond of blaming the lower judiciary are in for a surprise. In 2011, the lower judiciary for the 44.15 lac cases filed disposed off 46.06 lac cases . Hence more cases were disposed than were filed in 2011.

Yes, these statistics appear more optimistic than some credit ratings given to Greece. They do not factor in the backlog which already exists and the year on year increase in case filing. It is quite possible that the marginal advance that disposal over filing may tilt over as easily. Also these statistics are at a variance with the data which is contained in the National Crime Records Bureau which notes that in term of percentage disposal of IPC cases, disposal of cases by courts was 13.4% while remaining 84.6% cases were pending at the end of the year 2011. This can be contrasted with the pace of investigation of such crimes, where there were 32,43,783 cases for Police investigation during 2012 (including pending cases from previous year), out of which 23,95,036 (73.8%) cases of investigation were completed while 8,45,495 (26.0%) were pending at the end of 2012. Hence, if one is to look for causes of delay, they most directly can be attributed to delays by the Courts rather than the police.

The cause for such delay is the lack of proper staffing of judicial officers. Quite simply the supply has not matched the demand for justice. At the Chief Justices Conference in 2008 it was stated that about 3393 vacancies exist in the lower judiciary against the sanctioned strength. Though longer court hours, imposition of costs on adjournment and better docket management may in the interim contain pendency, the cure for it remains an increase in judicial officers.

Conviction rates overall

The disposal of cases only reflects one aspect of the concern with the criminal justice system. Mere efficiency in disposal does not guarantee the value of the determination. Though it would be wrong to term an acquittal as failure in itself, there is a presumption that the registration of a First Information Report (FIR) is on the basis of a prima facia disclosure of an offence. Moreover, when a charge sheet is filed in court after investigation is done by the police, then often there is a credible basis to question the eventual acquittal. This is because the charge sheet contains evidences gathered through investigation to back up the accusations contained in the FIR. Hence, if such evidences were not found, the Police may file a closure report, however if the situation was to the contrary a charge sheet is filed.

In this respect the overall statistics reveal a conviction rate of about 20.2% for the cases registered between 2010-2012 for crimes under the Indian Penal Code. It is important to bear that the convictions are based on cases registered in previous years as well, i.e. before 2010.

Rape in Particular

The background sets out a context to appreciate the figures with respect to the offence of Rape. Firstly with respect to the speed of the investigation. In this respect the police received 24,923 complaints of the offence of Rape in 2012. The same report released by the NCRB states that the police filed chargesheets in nearly 94% of the incidents of rape however, convictions were achieved in 26.4% of the rape cases pending before courts. There were 4,072 convictions and 11,351 acquittals.

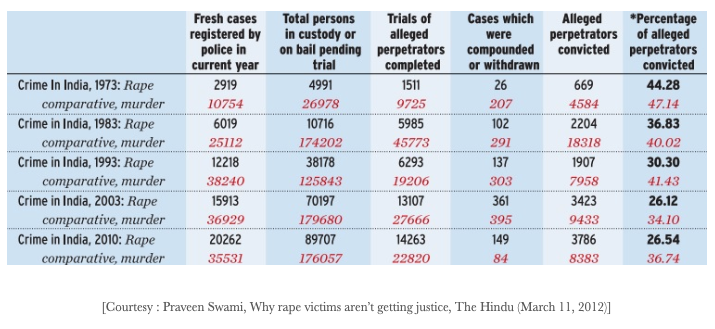

The conviction rate of Rape is often compared to Murder. This comparison is compelling since, it paints a wide disparity in the conviction rates, with convictions resulting in more than 40% of such trials. The table below sets out this well.

Undeniably it is the same police which is investigating these offences and it is the same judges who are delivering these verdicts. Then why such a disparity. Some may argue that both are different criminal offences. In murder, physical evidence in terms of the death establishes the commission of the crime. The same person would argue that to legally establish the lack of consent, cases of Rape the lack of consent becomes problematic. However this should not be the position after the Criminal Amendment Act, 1983 passed after the shameful decision in Tuka Ram v. State of Maharashtra (also popularly referred to as the Mathura Rape Case).

The amendment introduced Section 114-A in the Indian Evidence Act that imposed the burden of proving the existence of consent upon the accused in the aforesaid cases of aggravated rape as a specific exception to the rule of presumption of innocence. Even after the horrific gangrape in Delhi last year and the passage of the Criminal Amendment Act, 2013 rapes continue unabated. Here the trial of the Delhi Gangrape accused, has proceeded at a heightened pace due (registered on February 2, 2013) to media reporting of it. I would request to see this case in isolation and not part of the general trends noted above due to it being a high profile case.

Legal solutions, social problems

A better explanation for these conviction rates is explained by a sting operation carried by Abhishek Bhalla of Tehelka Magazine, called “the rapes will go on”. In this story 30 senior Delhi Police officers were shown to engage in widespread victim blaming. The chilling by lines of the article read as, “She asked for it. It’s all about money. They have made it a business. It is consensual most of the time.” This completely failed to appreciate the social stigma and even the damaged marriage prospects which result from reporting rape.

However it is convenient to blame the Police in isolation. This is a wider social problem where a man does not enter the kitchen or even flicks the switch of a washing machine. It is a society where women are not only systematically subjugated but viewed as chattel.

The police are not alone in this, it includes lawyers and judges as well. The same laws seem to work efficiently when applied in a society where women are ranked high on health and education indices. For instance, Mizoram, has a conviction rate of 96.6 percent even when it has the highest level of rape reported in India with, 9.1 per 100,000 residents (not a negative, since in other parts rape is under reported, on the contrary confirms the point on the societal structural supporting women).

Passing successive laws only caters to the human instinct for a quick solution. It is artificial. It is a placebo. The conceit of law acting in isolation is revealed by cases of Sati. Successive laws have been made since 1500 A.D. Without social pressure for a long time this remained mere text on paper. This is not to say that we do not need to cut down on delays. It is also not to suggest that further legal reforms are not necessary in terms of the recommendations of the J.S. Verma Committee. However let us recognize the nature of the beast. We cannot uproot rape by plucking a leaf in a courthouse.

Leave a Reply